HALIFAX – Lessons learned from the past will be pivotal on how Nova Scotians respond to the next global pandemic.

Dr. Allan Marble, a retired professor at both St. Francis Xavier and Dalhousie University’s medical school, will be speaking about the Spanish Flu and its impact on Nova Scotia in 1918-19 during a presentation at Ottawa House on July 29 at 2 p.m.

“Before the Spanish Flu outbreak there was almost no communication between the federal government and the province. There really wasn’t a federal health department up until this point and the provincial health department didn’t really do much,” he said. “After that, the Department of Health in Nova Scotia got bigger and spent a lot more money on dealing with issues like the flu more effectively.”

He said the flu also led Dalhousie University’s medical school to look more seriously at vaccination programs and public health issues and introduced courses in those areas.

Marble said the flu killed approximately 50 million people worldwide, including between 30,000 and 50,000 Canadians. In Nova Scotia, Marble estimates the number was about 2,000 people and considering Nova Scotia’s rural population the impact was felt throughout the province.

“During the four months the flu was at its peak in Nova Scotia, from about September to December 1918, there were about 2,000 killed, but the number of people who had the flu was about 10 times that,” Marble said.

The flu was brought into Canada by soldiers returning from the trenches of the First World War and it made its way into even the remotest communities in the country and the province, places such as Petit de Gras in Cape Breton and Lockeport in southwest Nova Scotia, where its residents contracted the flu from contact with Massachusetts fishermen.

Marble said the flu was different from other strains of influenza in that it tended to kill the young and healthy, especially between the ages of 15 and 40. Older Nova Scotians were spared mainly because they had built up an immunity to the flu following the Russian flu outbreak in the 1890s.

In studying the flu’s impact in Nova Scotia, Marble read newspapers from the period and was surprised at how little people talked about the flu in this province. He said there were numerous advertisements for cures and treatments, but little discussion on the flu’s impact.

“It was so traumatic that once it was over no one really wanted to talk about it,” he said. “Almost every family had someone who was impacted by it or knew someone who had it. It was like those people who fought on the front in the war. When they came back they didn’t want to talk about it when they came back.”

Marble, who for the last decade has been studying the flu’s impact on Nova Scotia, used vital statistics reports from that period as part of his research and information wasn’t made public until 2007 when they were transferred to the Nova Scotia Archives.

He went through all the death certificates from 1918 to 1919 to determine the impact of the flu and how it impacted people.

“I was able to put together a pretty good profile of the Spanish Flu in Nova Scotia. It’s something I couldn’t have done before 2007,” he said.

He said the flu essentially shut down communities as leaders attempted to control its impact and stop the outbreak.

“It was a very virulent disease. It spread rapidly,” he said. “It wasn’t a good experience. It dehydrated you and gave you severe headaches and diarrhea and if you died it was usually from pneumonia.”

Marble said part of the problem is the best scientific minds of the era thought the flu was bacterial as opposed to a virus. They were attempting to come up with vaccines and other treatments that were ineffective.

“It wasn’t until 1930 that we understood what a virus was,” he said. “There was no treatment for it whatsoever.”

The best treatment, he said, was isolation.

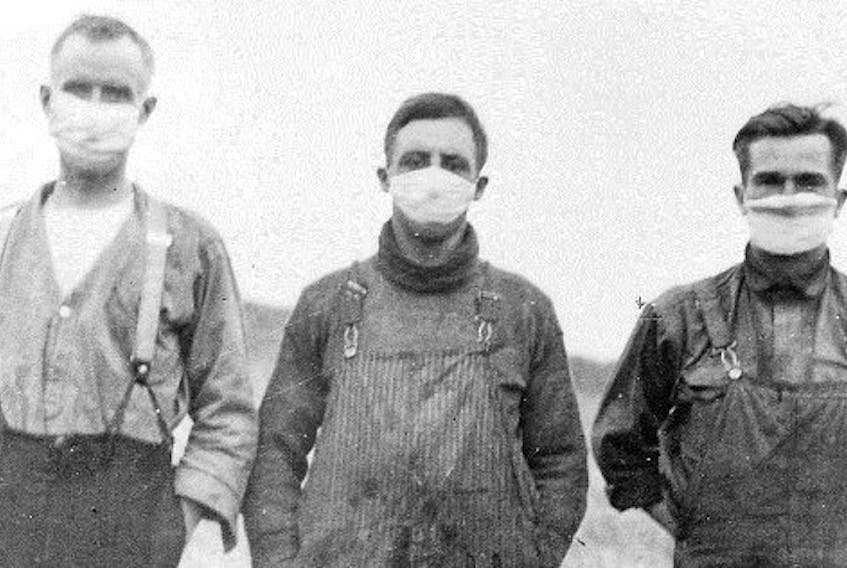

He said the decision was eventually made to close every school, pool hall, churches and public places for six weeks. The mayor of Halifax at the time was a doctor and he became aware of what was taking place in Boston the month previous could be reduced if people isolated themselves from others.

“He brought in that rule that everything had to be closed and he had the public health officer publish in the newspaper that these are the 14 things you can do to prevent yourself from getting the disease,” he said. “The main thing was to stay isolated and to wash your hands frequently.”

Marble said there were three waves to the Spanish Flu. The first wave hit the United States, the second wave hit Nova Scotia beginning in September 1918 and died out in April 1919. In January 1920, it came back for about three months.

“It eventually did die out,” he said. “What happens with these viral diseases is they mutate and the change in the virus itself makes it less virulent and less contagious. The virus is still with us today, but it doesn’t cause us any problems.”

Twitter: @ADNdarrell