It was Byron Butt's job to figure out what happened.

Seven hundred and twenty-three times, the retired RCMP traffic reconstruction investigator living in the Annapolis Valley responded to collisions over the decades. Quite often, it involved fatalities or serious injuries.

“Speed would be an issue. The environmental conditions would be an issue. The highway itself, the lay of the highway, that could be a factor,” he says noting drugs and alcohol plus speed was a fatal combination.

“That’s the equation for death.”

Going to a collision scene became routine. He knew what to look for. He knew what he had to do.

Still, it ate away at him.

“After you get home from the collision scene, then you sit down and you start to think, ‘Did I do the right thing?’, ‘Did I miss something?’, ‘Did I suggest something that I shouldn't have?’,” he says. “All those things used to go through my head and when you get home, you wouldn’t go to sleep, you’d be awake all night.”

He likened the thoughts in his head to a spin top - they just kept spinning and spinning.

At times, his job involved long hours on the road. A collision investigation scene may have been a 30-minute drive or three or four hours away. That, too, gave him a lot of time to reflect on what he would find.

“You’re thinking about how many people are involved, how many vehicles are involved, then the weather conditions and the road conditions and you have to try to get there in a safe and sound manner,” he says. “Everything is going through your mind. You’re wondering if it’s seniors, young people. And when you get there you see nothing but flashing lights.”

He would collect road and physical evidence to piece things together. It was important work — not just to find out the cause of that particular accident, but to also advance safety if trends were noted.

What he was also collecting along the way was post-traumatic stress disorder.

“That topic alone sneaks up on you and you don’t realize that it’s there until it’s too late. Every time now that I get a chance to talk to police officers or first responders, I always mention to them, if you’ve gone to a bad scene, get help," Butt says.

"This is what we’re trying to educate people and police organizations and agencies of. Look after your personnel. Have debriefs. I was in the force for 37 years. I had two debriefings in that 37 years.”

In his last two-and-a-half years in the RCMP, he knew there was a change coming over him, but he didn’t know what it was.

“It just snuck up and snuck up and snuck up,” he says, until he had three nights of nightmares and episodes that reinforced that it was time to seek professional and medical help. His wife, he says, was also critical in him getting the help he needed.

Safe retreat

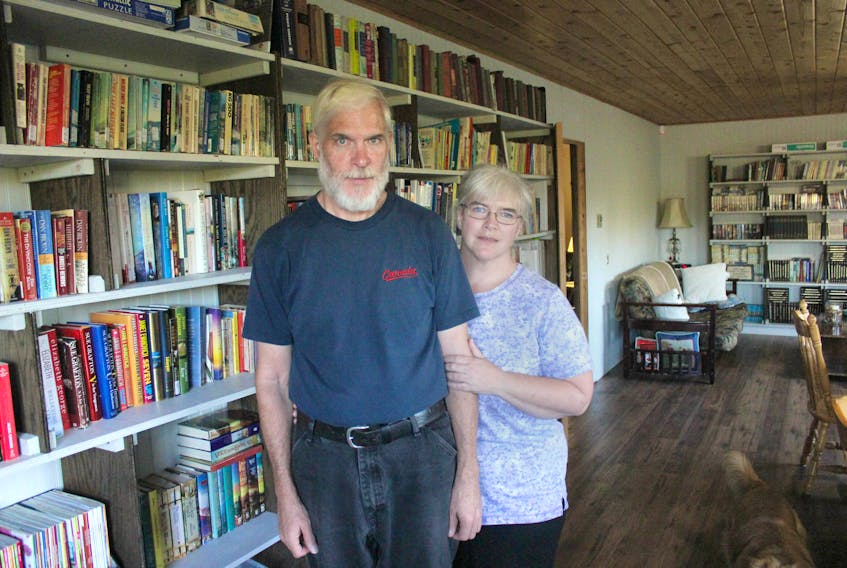

Helping others is also what Bob and Johan Grundy of Rally Point Retreat in Sable River, N.S. do. Years ago, they opened up their ranch-style home as a retreat for military personnel and first responders who are dealing with post-traumatic stress.

After hearing from others that a need for this type of escape existed, they wanted to offer people a quiet, unassuming place to relax.

Their wide-open home and 320 acres of mostly wooded paradise fit the bill.

Bob Grundy, who served as a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force, knows from experience the toll PTSD takes.

“It’s amazing how many times that has been the end of a career,” he says. “Usually, there’s been a child involved. Especially fatal accidents involving children.”

Often, it’s the cries from the scene that people can’t shake.

Grundy and his wife offer strictly peer support.

“What we get the chance to do is provide them with the basics of what PTSD will manifest itself as and it’s always a ‘could’ thing, there’s never a certainty that’s it’s going to appear ‘just like this,’” he says.

“Even two people from the same branch of service are going to experience it differently because it’s all based on how we developed into adults, what traumas were in their life ahead of this time. What caused them to become a paramedic, a firefighter, a police officer. Some people came in completely naive, perhaps, of what they can see and that could have a totally different effect on them. Someone else might be more experienced, it may not affect them as badly, or maybe it will affect them even more.”

The retreat opened in 2015 but Grundy says the word about it is not getting out as quickly as needed. Then again, he says, maybe baby steps were the way to go.

“It’s been pointed out to me numerous times by some of our many supporters, if you built it up too fast, could you have stayed on top of it? And the answer would have been no,” he says. “There’s only Jo and I here. This is a 365-day a year, no-vacation job, essentially. If we have guests in-house, they can’t predict that they’re going to trigger. As they get more relaxed and they can talk freer, we have guests who are returning after we walk in the woods who we’ve sat and talked for a while and they’re like, my therapist doesn’t even know about this yet.”

It can make a difference when you're not under that one-hour appointment time crunch.

“Nobody feels that they’re ever up against a wall, unless they purposely put themselves there,” Grundy says, noting that often, it hasn’t just been any one single incident that has triggered PTSD for first responders, but rather a build-up. You never know which straw may finally be the one to break things.

“The breakdown starts slowly, with no reveal until it’s right there,” Grundy says.

Having responded to motor vehicle collisions is part of this, he says, including ones where excessive speed have been a contributing factor.

“I’d urge people to all to slow down. It’s easier to gauge how much time it’s going to take you to get somewhere if you follow the speed limit,” he says. “If you have an accident how much time have you saved by driving over the speed limit? It's all gone.”

Seek help

Butt has visited Rally Point Retreat and is part of a support group that meets in Greenwood for members of the armed forces who have PTSD.

“If, during the week, I run into a situation that I can’t handle or I’m having flashbacks - which that occurs a lot, especially when you’re driving on the road and you see the crosses on the side of the road,” Butt says it helps to know he has support he can turn to. He urges others to do the same.

“I speak to a lot of police officers who I see are going through the same thing as when I began,” he says. “One of the biggest factors is we, as police officers, we think we’re too strong and don’t want to get help, or are afraid to get help, afraid someone is going to say something.”

Don’t let your ego get in the way of seeking help, he says.

“It can put you in real danger.”

Read more about our Need for Speed, its risks and consequences