Before Nova Scotians plunge into fracking they need to ask themselves the key question, and that’s almost always: Why?

People are inclined to get stuck on how. They want industry or government assurances that hydraulically fracturing rocks deep underground to release the gas embedded within can be done “safely,” whatever that means.

The better question is: Why do it at all?

It’s a question that either goes unanswered or worse, the answer betrays a 19th century attitude that too many East Coast politicians dragged through the 20th and into the 21st century. They’d pillage the village and sell off the booty to the first taker.

READ MORE:

• Fracking fissures not broken at Pugwash debate

• The case against fracking: Process more of a bust than a boom for Nova Scotia

• The case for fracking: Delays in decision costing Nova Scotians millions

It’s the policy of John Lohr and, to varying degrees, other candidates for Nova Scotia’s Conservative Party leadership. They dress it up a little because admitting they’d sell out the province for a few bucks and some fleeting jobs is lousy politics even when only Tories can vote, like in the leadership.

Fellow candidate Cecil Clarke wants royalties from onshore gas to stay in the fracking communities where folks could roll around in their new-found wealth for the year or two it lasts.

The depth of the Tories’ fracking policy is better suited to surface mining than to drilling a kilometre or more into the earth.

If the pro-fracking Conservatives can cough up a coherent energy strategy that benefits Nova Scotia longterm by developing onshore gas, they earn a listen. Until then, tune them out and if they carry their half-cracked policy into the next election, think seriously about the other boxes on your ballot, because the Tories are peddling the old “drawers of water, hewers of wood” economic orthodoxy that has anchored the East Coast economy to the bottom for generations.

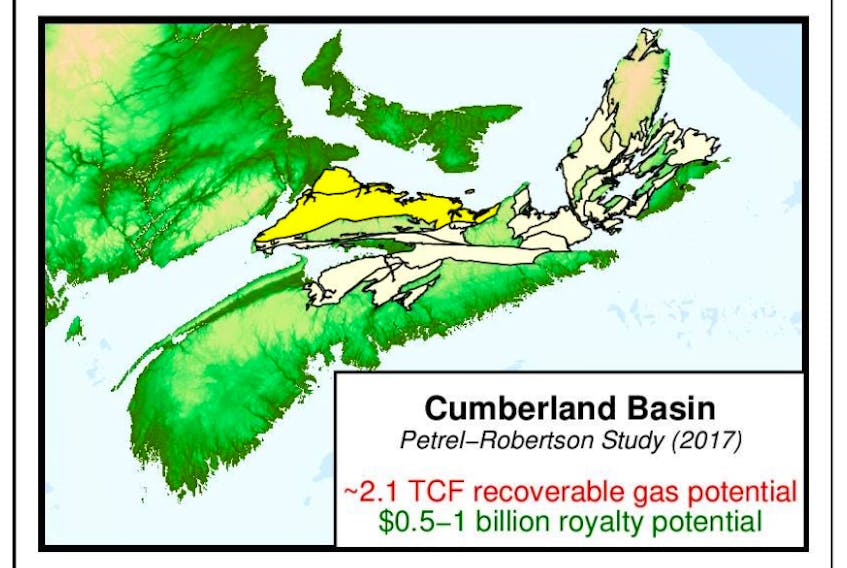

Lohr likes to tell folks that the Atlas report shows gas locked up in the rocks upon which Nova Scotia sits is worth somewhere between $20 billion and $60 billion. The broad range of the estimate tells us that no one knows how much gas is down there or if it can be extracted at a cost that pays off.

Assuming there are economically-viable deposits of gas trapped in the rocks of Northern Nova Scotia, what are we going to do with it once it’s released? If the answer is ‘sell it,’ take the jobs and royalties and run, see above.

Nova Scotia got jobs and royalties out of the Sable offshore gas development, which dwarfs any imaginable fracking program.

Now that Sable is winding up, it looks like the lasting benefits might be an empty pipe and some bandwidth for rural Internet users. The McNeil government sunk most of the windfall from past-due royalty payments into what will become subsidies to get IP companies to extend decent Internet service to rural Nova Scotia. While that’s a worthwhile objective, it hardly meets the lofty expectations for Sable that Nova Scotians were sold.

In the early days, Sable was going to set Nova Scotia free from oil furnaces and coal-fired power generators. It did neither. Gas was only available in a few pockets across the province.

Most of Sable’s gas was pushed into a pipeline and pumped to the states where it was sold at the going rate. If that’s the plan for shale gas, leave it in the rocks.

Nova Scotia’s onshore gas reserves could be developed to advance energy self-sufficiency, security and lower CO2 emissions. If that’s the plan, it might be worth having the discussion.

But past is prologue, and none of those things happened with Sable. Nova Scotia Power’s conversion from oil and coal to more environmentally-friendly gas was a token effort at best.

Fracking carries risks. The extent of the peril depends on who you ask, but the process consumes huge volumes of water that emerge contaminated and must be disposed of or held in vast toxic lagoons.

Nova Scotia currently has a rather informal fracking moratorium in place, but the province is drafting regulations “that give effect to our moratorium on high-volume hydraulic fracturing.”

The American Public Health Association updated its position a year ago, stating there is empirical evidence that fracking harms both nature and people and “we have no idea what the long-term effects might be.”

Given all that, Nova Scotians need a better reason to allow fracking than the promise of some short-term work and extra cash from selling gas.